NAWL and Luke's Place Brief on Bill C-78

An Act to amend the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act and to make consequential amendments to another Act

Bill C-78 was the first legislative update to the Divorce Act in more than 20 years. The bill modernized the Act by replacing the language of custody and access with legal principles focused on the parent-child relationship; providing greater guidance to courts and parents for the determination of the best interests of the child; addressing family violence; providing a framework for the relocation of a child; and simplifying processes for the recalculation and enforcement of family support obligations.

In 2018, NAWL and Luke’s Place submitted a parliamentary brief on Bill C-78 to the House of Common’s Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights. The brief was endorsed by 31 organizations from across the country. On November 19 and 21, 2018, over a dozen feminist and equality seeking organizations appeared before the Committee. When the Bill moved to the Senate, NAWL appeared again before the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs on June 6, 2019, alongside the Fédération des maisons d’hébergement pour femme and Regroupement des maisons pour femmes victimes de violence. Bill C-78 received Royal Assent and became law on June 21, 2019.

Organizational Endorsements

Discussion Paper

Brief on Bill C-78

Senate Committee Observations

Press Release

Bill C-78 Coalition Timeline

May 22, 2018

July 11, 2018

July 30, 2018

October 4, 2018

November 19, 2018

November 21, 2018

December 7, 2018

February 6, 2019

February 19, 2019

April 11, 2019

July 3, 1984

June 6, 2019

June 21, 2019

Overview of the Legislation

Briefs Submitted by Coalition Members to the Standing Committee on Justice and Human Rights

- Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic

- Canadian Women's Foundation

- Fédération des maisons d'hébergement pour femmes du Québec

- Harmony House

- Manitoba Association of Women's Shelters

- Ottawa Coalition to End Violence Against Women

- Regroupement des maisons pour femmes victimes de violence conjugale

- South Asian Legal Clinic of Ontario

- West Coast LEAF

- Women's Legal and Education Action Fund

- Women's Shelters Canada

NAWL's Appearance before the Standing Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs

Introduction

This is a joint brief on Bill C-78: An Act to amend the Divorce Act, the Family Orders and Agreements Enforcement Assistance Act and the Garnishment, Attachment and Pension Diversion Act and to make consequential amendments to another Act (hereinafter Bill C-78) by Luke’s Place and the National Association of Women and the Law (NAWL). It is informed by multiple consultations with feminist lawyers, academics, advocacy and frontline service organizations.1This Brief was prepared by Suki Beavers and Anastasia Berwald (NAWL) and Pamela Cross (Luke’s Place). NAWL and Luke’s Place gratefully acknowledge the many contributions that informed the development of this brief, including those made by the following organizations: Action Ontarienne contre la violence fait aux femmes; the Barbra Schlifer Commemorative Clinic, the BC Society of Transition Houses, the Canadian Council of Muslim Women, the Canadian Women’s Foundation, the DisAbled Women’s Network of Canada, Femmes Autochtones du Québec, Harmony House, LEAF (Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund), Ontario Association of Interval Transition Houses, the Native Women’s Association of Canada, Ottawa Coalition to End Violence Against Women , RISE Women’s Legal Centre, the South Asian Legal Clinic, Vancouver Rape Relief and Women’s Shelter, West Coast Leaf, Women’s Shelters Canada. NAWL and Luke’s Place also gratefully acknowledge contributions made by the following law firms and individuals: Athena Law, Equitas Law Group, Jenkins Marzban Logan LLP, Suleman Family Law, Professor Emerita Susan Boyd, Rachel Law, Hilary Linton, Professor Linda Neilson and Glenda Perry. Finally, special thanks to Lisa Cirillo, Lorena Fontaine, Martha Jackman, Anne Levesque, Cheryl Milne and Zahra Taseer (NAWL), and Carol Barkwell (Luke’s Place) for their contributions.

Luke’s Place is a community organization in Durham Region, Ontario, that works to improve the family court experiences and outcomes of women leaving abusive relationships. This work includes both direct service delivery to women in Durham Region and systemic work such as research, resource development, training and education and law reform advocacy at the provincial and national levels.

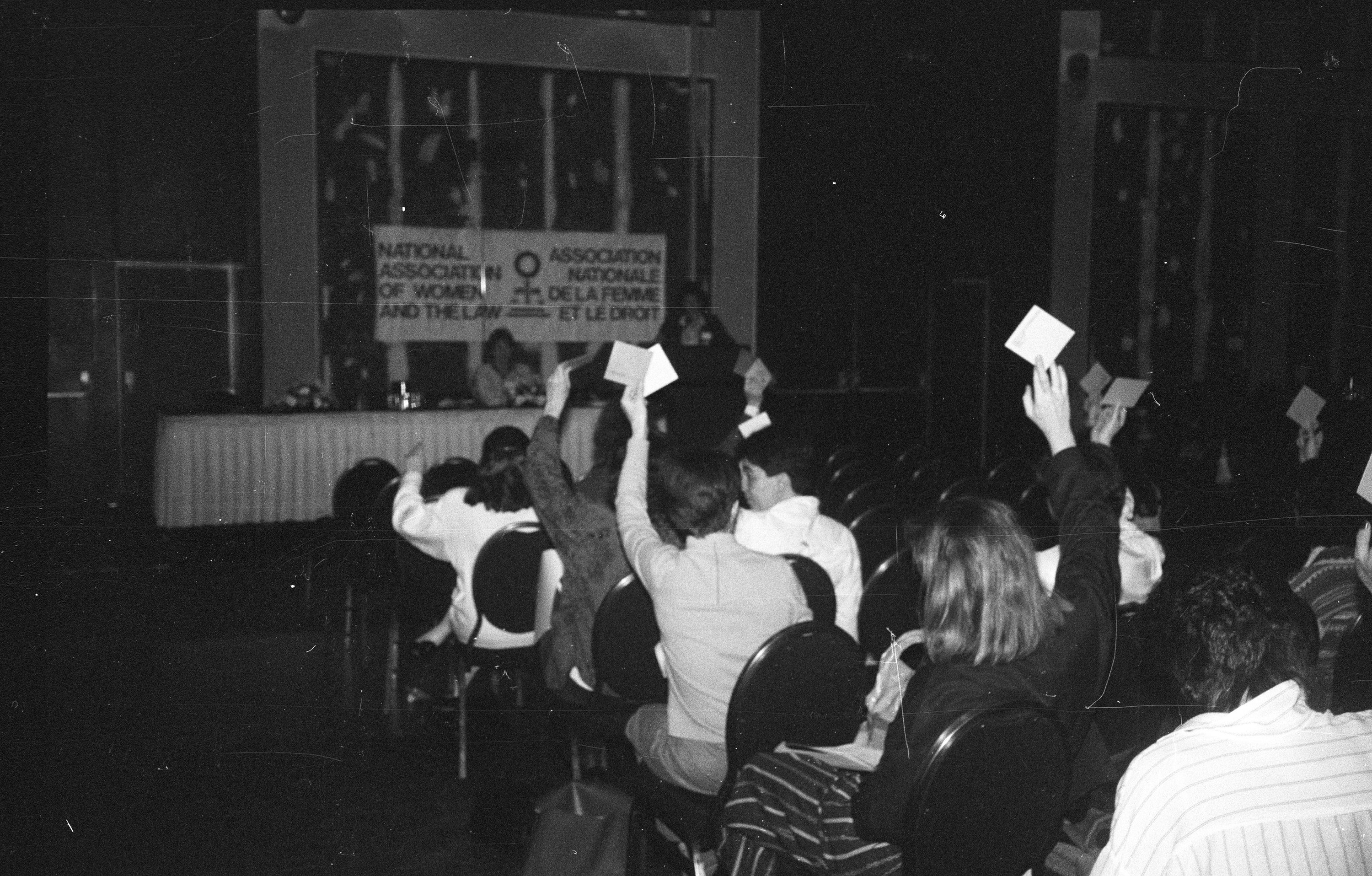

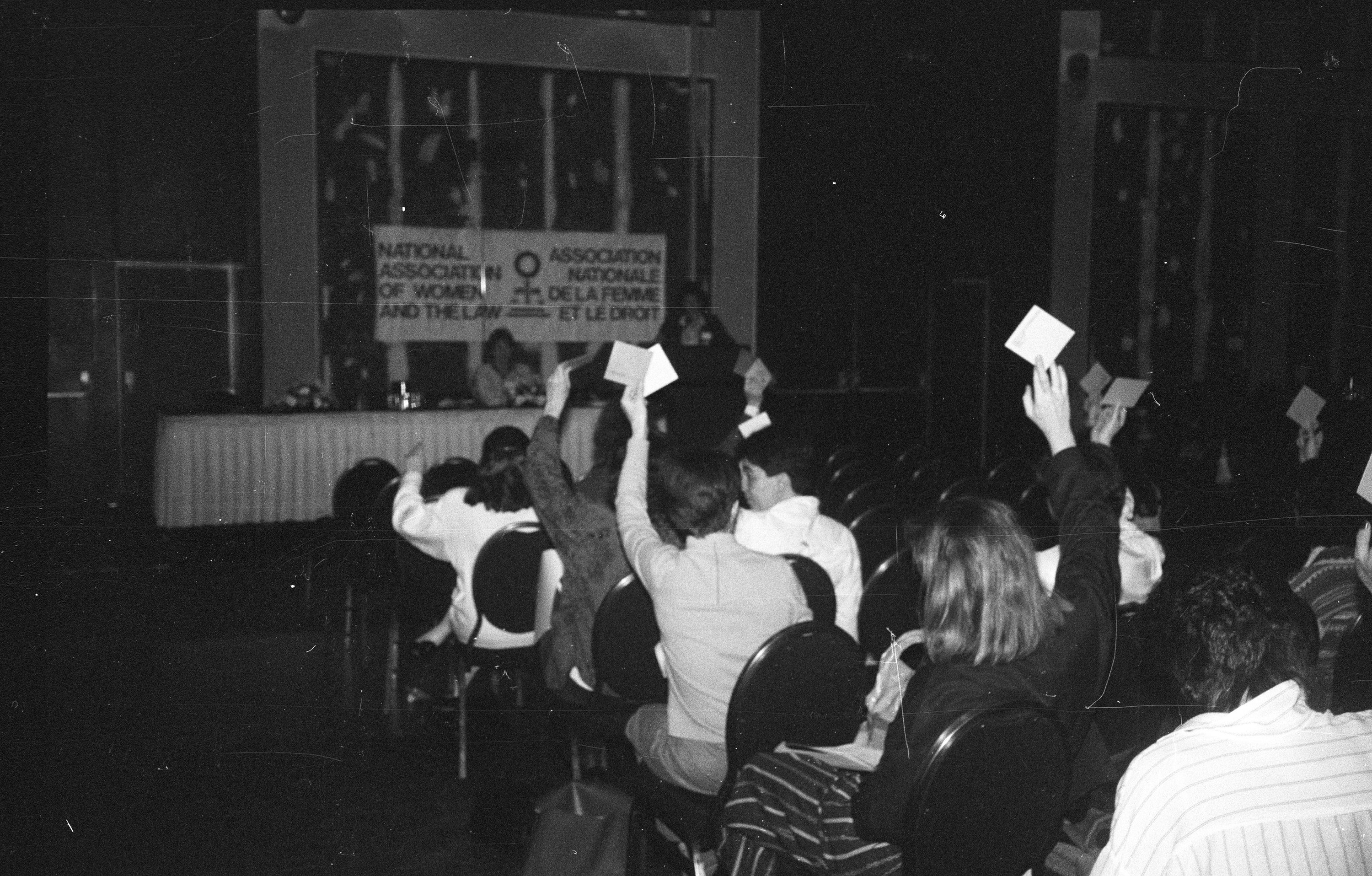

NAWL is an incorporated not-for-profit feminist organization that promotes the equality rights of women in Canada through legal education, research, and law reform advocacy. NAWL has a long history of work and advocacy on women’s rights in the context of the separation and on the Divorce Act in particular, and on violence against women.

Both Luke’s Place and NAWL use an intersectional and gender-based analysis that focuses on the lived realities of women in all their diversity. Other factors such as race, Indigenous identity, ethnicity, religion, gender identity or gender expression, sexual orientation, citizenship, immigration and refugee status, geographic location, social condition, age, and disability influence women’s experiences. This is true in the context of violence against women, family violence, and divorce.

We recognize the devastating effects settlers’ colonialism has had on Indigenous women and communities. Any discussion of violence against women must consider these ongoing impacts as well as the actions and absence of actions by governments and individuals that continue to perpetuate them.

In this Brief, we have used gender-specific language to refer to those who are harmed by violence within the family and those who cause that harm. We believe it is important to acknowledge that, in Canada, women in all their diversity, and transgender, queer and gender non-conforming people are overwhelmingly those who are subjected to abuse, and men are primarily those who engage in abusive behaviour. We also acknowledge the diversity of women and families in this country and acknowledge the continued adverse impacts of misogyny, homophobia, transphobia and heteronormative culture.

Comments

Context for Recommendations

At the outset, we want to recall the international and domestic obligations of the Federal Government in relation to the rights of all Indigenous peoples in Canada, and to Indigenous women specifically. The Government of Canada has committed to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples. Reconciliation is only possible through the renewal of the relationship between Indigenous peoples and Canada, on a nation-to-nation basis. This undoubtedly includes the consultation of Indigenous peoples, including indigenous women, during the law-making process, whenever new laws may affect them. To date, there is no evidence that the Department of Justice has engaged in meaningful consultation with Indigenous women’s groups on the potential impacts of C-78 on Indigenous women, their children, families and communities. We urge the Federal Government to do so prior to the finalization and enactment of C-78, in order to ensure the cultural heritage, safety, security, autonomy and rights of Indigenous women and their children are respected, protected and fulfilled, and not further endangered or violated by any impacts (direct or indirect) of any of the provisions of C-78.

As mentioned, there are many welcome additions and changes in Bill C-78. Luke’s Place and NAWL support having children and their well-being remain at the centre of the Divorce Act. We commend the important objective of reducing conflict, but note that care must be taken to ensure that conflict and family violence are not conflated, as this can be very dangerous. The requirements that are appropriate to place on parents in nonviolent, albeit conflictual, situations should differ from those that need to be put in place when an abused woman is involved in a divorce proceeding. Therefore, the majority of our recommendations focus on proposing specific changes that are required to help ensure that Bill C-78 will truly protect women at the end of an abusive relationship, as well as their children.

Our analysis identifies aspects of Bill C-78, including those that demand communication and cooperation between spouses, and the unintended ways in which some aspects of communication and cooperation expected of parents during divorce proceedings may obscure the realities of family violence and risk endangering women and children. The broad definition of family violence already included in the Bill demonstrates an understanding that family violence is complex and pervasive, and it is important that all aspects of the Bill are framed accordingly and with an understanding that the complexities and pervasiveness of the impacts of past violence, and indeed the ongoing occurrences of violence themselves, do not end simply because divorce proceedings begin. The evidence is clear that violence by husbands often intensifies in the months following a separation, making them the most lethal for many abused women. Consequently, requiring that mothers continue to communicate and cooperate with an abusive spouse is not only inappropriate, it is dangerous, and potentially lethal. Nonetheless, mothers who are legitimately incapable of or unwilling to cooperate with an abusive spouse are frowned upon by the courts and may even loose custody of the children to the abusive spouse. Therefore, cooperation and communication provisions need to be flexible and clearly indicate that they may not be appropriate and should not be required in cases where there has been any history of family violence.

The definition of family violence included in Bill C-78 rightly excludes self-defence. However, cases demonstrate a lack of understanding of the varieties of ways women resist and survive family violence. We hope that identification of patterns of coercion and control will help courts understand the dynamics of family violence and that acts of resistance and survival from abused women will cease to be considered acts of family violence.

We are in favour of maintaining rather than changing the habitual and clear terms of ‘custody’ and ‘access’ in the Divorce Act. In addition, we propose that the decisions that the parent with custody has the authority to make, and the types of decisions that can also be made by the parent with access, should both be further clarified in Bill C-78. We understand the sentiment behind the proposal to introduce new terms to replace ‘custody’ and ‘access.’ In principle, we agree that trying to shift the focus in divorce proceedings away from the perception that one parent wins a custody battle and the other loses it, to a focus on cooperation between parents so that the best interests of the child prevail, seems positive in cases where there has not been any violence. Unfortunately, the risks associated with the introduction of new language that will be subject to much interpretation and debate far outweigh the desired benefits, well-intentioned though they are. As we heard from lawyers and advocates who have been working with similar new language in some provincial family law regimes, there is no compelling evidence that the new language introduced has actually been effective in reducing conflict when the issues of custody, access and decision-making are in dispute. There is also legitimate reason to be concerned that this new language will cause interpretation conflicts in international matters, as it differs from the language used in the Hague Convention. This may prevent Canada from fulfilling its duties under the Convention. Moreover, the experiences of too many women who have been in abusive relationships reflect that abusive men exploit every angle of uncertainty and ambiguity they can find. Every ambiguity introduced into law can be turned into an opportunity for abuse, harassment and undermining of the mother. Therefore, it is safer for children and their mothers to have a clear, unambiguous allocation of custody, and clarity about who has the authority to make specific decisions about what is in the best interests of a child.

We have similar concerns about the proposed mandatory requirement that family dispute resolution processes be encouraged. Of course, some women find such processes empowering and/or better suited to their needs. However, family dispute resolution processes are not always better and particularly in cases involving family violence, they may not be appropriate at all. The flexibility of family dispute resolution processes serves some families extremely well, but in other circumstances, they can provide abusive partners with an opportunity to manipulate and continue being abusive. The Divorce Act should reflect and respect women’s autonomy and agency, and provide them with all the tools necessary to make free and informed decisions about which process is better and safer for them. Thus, rather than requiring legal advisers always ‘encourage’ dispute resolution, we recommend that Bill C-78 be revised to require all legal advisers to fully inform spouses about all processes available to them. This change will ensure that all women get information on the full range of processes available, so they can make a meaningful choice about which type of process is best suited to their circumstances and needs. We believe the current mention of “appropriateness” in the provision is not sufficient and will lead to family dispute resolution being the default process, including in cases of family violence in which it may be dangerous.

Finally, harmful myths and misconceptions about the realities and the dynamics of family violence still influence family law processes and decisions. Therefore, education on family violence and gender equality must be a crucial part of the reform of the Divorce Act, and implementation of Bill C-78. Consequently, Luke’s Place and NAWL recommend that Bill C78 include education requirements for all actors in the family law system (including lawyers, legal advisers, paralegals, mediators, arbitrators, judges, etc.).